About

From the team behind Penguin Random House Canada’s award-winning magazine Hazlitt, Strange Light publishes unpredictable, innovative authors telling personal and provocative and experimental stories, even—and especially—those that defy easy categorization. With a list composed of both Canadian and international titles, Strange Light publishes vital voices, new and established alike, that command attention and curiosity, offering readers the delight of the unexpected.

People

Lanny

Max PorterFrom the award-winning author of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers comes a dark, playful, propulsive novel about an ethereal young boy who attracts the attention of a mythical, menacing force.

There's a village an hour from London. It's no different from many others today: one pub, one church, red-brick cottages, some public housing, and a few larger houses dotted about. Voices rise up, as they might anywhere, speaking of loving and needing and working and dying and walking the dogs. This village belongs to the people who live in it, to the land and to the land's past.

It also belongs to Dead Papa Toothwort, a fabled figure local schoolchildren used to draw green and leafy, choked by tendrils growing out of his mouth, who awakens after a glorious nap. He is listening to this twenty-first-century village, to its symphony of talk: drunken confessions, gossip traded on the street corner, fretful conversations in living rooms. He is listening, intently, for a mischievous, enchanting boy whose parents have recently made the village their home. Lanny.

With Lanny, Max Porter extends the potent and magical space he created in Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. This brilliant novel will enrapture readers with its anarchic energy, with its bewitching tapestry of fabulism and domestic drama. Lanny is a ringing defense of creativity, spirit, and the generative forces that often seem under assault in the contemporary world, and it solidifies Porter's reputation as one of the most daring and sensitive writers of his generation.

In his bold second novel, Porter combines pastoral, satire, and fable in the entrancing tale of a boy who vanishes from an idyllic British village... This is a dark and thrilling excavation into a community’s legend-packed soil.

Reading Lanny is like going to the back of the garden to find the exact spot where magic and menace meet. It's delightful and dark stark and stylish and as strange as it is scary—I loved it.

In Lanny Max Porter has expanded on his innovative hybrid mode while remaining faithful to our species-wide tradition of storytelling through myth, magic, and parable, but also through the harrowing minutiae of being alive in the trying hours of a small town ruptured by loss. The result is a powerful yet tender reclamation of the imagination, love, and artmaking—all of it a brilliant defense of the outsider’s tenuous foothold in society.

I Become a Delight to My Enemies

Sara PetersDark, cutting, and coursed through with bright flashes of humour, crystalline imagery, and razor-sharp detail, I Become a Delight to My Enemies is a gut-wrenchingly powerful, breathtakingly beautiful meditation on the violence and shame inflicted on the female body and psyche.

An experimental fiction, I Become a Delight to My Enemies uses many different voices and forms to tell the stories of the women who live in an uncanny Town, uncovering their experiences of shame, fear, cruelty, and transcendence. Sara Peters combines poetry and short prose vignettes to create a singular, unflinching portrait of a Town in which the lives of girls and women are shaped by the brutality meted upon them and by their acts of defiance and yearning towards places of safety and belonging. Through lucid detail, sparkling imagery and illumination, Peters' individual characters and the collective of The Town leap vividly, fully formed off the page. A hybrid in form, I Become a Delight to My Enemies is an awe-inspiring example of the exquisite force of words to shock and to move, from a writer of exceptional talent and potential.

In The Dream House

Carmen Maria MachadoA revolutionary memoir about domestic abuse by the award-winning author of Her Body and Other Parties.

In the Dream House is Carmen Maria Machado's engrossing and wildly innovative account of a relationship gone bad, and a bold dissection of the mechanisms and cultural representations of psychological abuse. Tracing the full arc of a harrowing relationship with a charismatic but volatile woman, Machado struggles to make sense of how what happened to her shaped the person she was becoming.

And it's that struggle that gives the book its original structure: each chapter is driven by its own narrative trope—haunted houses, erotica, bildungsroman—in which Machado holds the events up to the light and examines them from different angles. She looks back at her religious adolescence, unpacks the stereotype of lesbian relationships as safe and utopian, and widens the view with essayistic explorations about the history and reality of abuse in queer relationships.

Machado's dire narrative is leavened with her characteristic wit, playfulness, and openness to inquiry. She casts a critical eye over legal proceedings, Star Trek and Disney villains, fairy tales, as well as iconic works of film and fiction. The result is a wrenching, riveting book that explodes our ideas about what a memoir can do and be.

Coming Soon

Coming Soon

Hello Pig

Anshuman IddamsettyA blazing pursuit of a trauma-free future for the fat body.

"An enduring cultural fiction is that life begins when a fat person loses weight. Once the pounds are shed, we are told, does the story truly begin. You write this today with the clarity of heaven: your life began when you became fat."

In 2015, Anshuman Iddamsetty decided he wanted to, in his words, occupy as much space as possible, announcing this desire in a much-lauded essay, "Swole Without a Goal." At the time, his journey involved serious weightlifting, but what, he thought, if fitness hadn't been part of it? Would readers have been quite so moved if his story hadn't contained the familiar whiff of so-called self-improvement?

Soon after, Anshuman's life changed in ways dramatic and mundane: his father, a tall, fit man, died suddenly; Anshuman's own fattening, meanwhile, continued apace, to the disgust of his surviving family members. Amidst great personal change, a family history steeped in the inherited meekness of India's caste system and the desire for the quiet life of the "model minority," and within a contemporary culture where even ostensible progressives mock and ridicule the appearance of political foes like Donald Trump and Rob Ford, Anshuman proposes a new way: fatness as a path forward from grief. Fatness as a rejection of the cult of "wellness" that, in a world of great economic and occupational precariousness, has become the greatest flex of privilege of all. Fatness as a challenge to the very idea that the body is something we should—or even can—control and bring to heel in the first place.

In riveting, sexy, funny, and devastating prose, Anshuman's debut book of non-fiction blends memoir, cultural criticism and journalism, taking him from being the fattest person on a business trip to Fiji to posing nude for a variety of photographers to exploring the world of furries. What he ends up with is a truly radical document: a book that makes the case for the fat body as a point of pride, a point of power, a tool to reclaim territory, and a way to stake a claim on a future that, until now, has only ever been promised to a privileged few.

Pure Life

Eugene MartenA harrowing, intense, powerful new novel that reads like a classic, from one of the great writers of his generation.

Nineteen battles his way into the pros, becomes the quarterback, becomes the myth. Marries the owner’s daughter, touches greatness few will ever dream of, retires into what he assumes will be the promised afterlife of days on the golf course, celebrity endorsements, and cushy real estate investments. But markets tank, family disintegrates, fame fades, and the holes in his mind and memory from a career of punishment on the field become too large and frightening to ignore. When he hears of a miracle brain damage treatment forbidden in the U.S., he travels to the Mosquito Coast of Honduras in search of a chance to restore himself to the man he was. Instead, he finds himself on a journey that plunges him into a darkness more violent and horrific than he could have possibly imagined—at once a fight for his life and to hold onto the shards and fragments of the life he’s fighting for.

A sports saga, sprawling thriller, and existential reckoning with the rot at the core of the west, told by an unheralded, singular master, Pure Life is a daring, complex, and brutal confrontation with and demolition of our modern myths in the most primal of settings—one as perilous as it is imperiled.

Modern Whore

Andrea Werhun and Nicole BazuinOh, the places a whore will go: Strip clubs, four-star hotels, stinking basement apartments, luxury cottages. A striking memoir by Andrea Werhun and Nicole Bazuin documents Andrea's sex work career in lush photography and powerful words—in all its slippery, sexy, silly and sometimes heartbreaking glory.

Andrea Werhun's sex work career gave her money, freedom, joy, and a lot of dick. A natural performer, she revelled in the opportunity to invent Mary Ann, her escort counterpart, and introduce her to men all over the city. She whores, she learns, she writes it all down, and then, as per a signed document she handed to her Catholic mother in her early twenties, she quits. To become a stripper.

Andrea and Nicole revisit the idea of the modern whore, with the enhanced perspective of Andrea's experience at the strip club. This new, engorged edition of the sold-out memoir-cum-art book expands on the original concept—a series of vignettes exploring the many identities sex workers adopt in the service of their clients and in the eyes of the public—in both a literal and literary way. But Andrea doesn't shy away from the serious side of sex work, either, exploring the risks sex workers take, and the rights our culture is constantly taking away from them.

This series of stories and portraits investigate the many ways we imagine—and mistake—the modern whore. It's Playboy if the Playmates were in charge.

Indelicacy

Amina CainAn intimate, elegant, and deceptively sinister story of what a woman will do to take control of her life.

A woman aspiring to a contemplative life faces innumerable obstacles—cultural, financial, sexual, and metaphysical—that stand between her and the freedom to live as she desires.

In "a strangely ageless world somewhere between Emily Dickinson and David Lynch" (Blake Butler), a cleaning woman at a museum of art nurtures aspirations to do more than simply dust the paintings that surround her. She dreams of having the liberty to explore them in writing, and so must find a way to win herself the security and time to use her mind. She escapes her lot by marrying a rich man sympathetic to her "hobby," but having gained a husband, a house, high society, and a maid, she finds that her new life of privilege is no less constrained. Not only has she taken up different forms of time-consuming labor—social and erotic—but she is now, however passively, forcing other women to clean up after her. Perhaps another and more drastic solution is necessary?

Reminiscent of a lost Victorian classic in miniature, yet taking equal inspiration from such modern authors as Jean Rhys, Octavia Butler, Clarice Lispector, and Jean Genet, Indelicacy is at once a ghost story without a ghost, a fable without a moral, and a down-to-earth investigation of the barriers faced by women in both life and literature. It is a novel about seeing, class, desire, anxiety, pleasure, friendship, and the battle to find one's true calling.

This Red Line Goes Straight To Your Heart

Madhur AnandAn experimental memoir about Partition, immigration, and generational storytelling that weaves together the poetry of memory with the science of embodied trauma using the imagined voices of the past and the vital authority of the present.

We begin before the red line is drawn across Punjab, with a man off balance: one in one thousand, the only child in town whose polio leads to partial paralysis. We meet his future wife, on the wrong side of the red line that has now been drawn, chanting Hey Rams for Gandhiji and choosing education over marriage. On one side of the line that divides this book, we follow them as their homeland splits in two and they are drawn together, moving to Canada and raising their children in mining towns, on Indigenous reservations, in crowded city apartments. And when we turn the book over, we find the daughter's tale—we see how the rupture of Partition, the asymmetry of a father's leg, the virus of a mother's rage, makes its way to the next generation. Told through the lenses of biology, physics, history and poetry, this is a memoir that defies form and convention to immerse the reader in the feeling of what remains when we've heard as much of the truth as our families will allow, and we're left to search for ourselves among the pieces they've carried with them.

Red X

David DemchukA hunted community. A haunted author. A horror that spans centuries.

Men are disappearing from Toronto's gay village. They're the marginalized, the vulnerable. One by one, stalked and vanished, they leave behind small circles of baffled, frightened friends. Against the shifting backdrop of homophobia throughout the decades, from the HIV/AIDS crisis and riots against raids to gentrification and police brutality, the survivors face inaction from the law and disinterest from society at large. But as the missing grow in number, those left behind begin to realize that whoever or whatever is taking these men has been doing so for longer than is humanly possible.

Woven into their stories is David Demchuk's own personal history, a life lived in fear and in thrall to horror, a passion that boils over into obsession. As he tries to make sense of the relationship between queerness and horror, what it means for gay men to disappear, and how the isolation of the LGBTQ+ community has left them profoundly exposed to monsters that move easily among them, fact and fiction collide and reality begins to unravel.

The Death of Francis Bacon

Max PorterA great painter lies on his deathbed, synapses firing, writhing and reveling in pleasure and pain as a lifetime of chaotic and grotesque sense memories wash over and envelop him.

In this bold and brilliant short work of experimental fiction by the author of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers and Lanny, Max Porter inhabits Francis Bacon in his final moments, translating into seven extraordinary written pictures the explosive final workings of the artist's mind. Writing as painting rather than about painting, Porter lets the images he conjures speak for themselves as they take their revenge on the subject who wielded them in life.

The result is more than a biography: The Death of Francis Bacon is a physical, emotional, historical, sexual, and political bombardment--the measure of a man creative and compromised, erotic and masochistic, inexplicable and inspired.

little scratch

Rebecca WatsonIn the formally innovative tradition of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers and Ducks, Newburyport comes a dazzlingly original, shot-in-the-arm of a debut that reveals a young woman's every thought over the course of one deceptively ordinary day.

She wakes up, goes to work. Watches the clock and checks her phone. But underneath this monotony there's something else going on: something under her skin.

Relayed in interweaving columns that chart the feedback loop of memory, the senses, and modern distractions with wit and precision, our narrator becomes increasingly anxious as the day moves on: Is she overusing the heart emoji? Isn't drinking eight glasses of water a day supposed to fix everything? Why is the etiquette of the women's bathroom so fraught? How does she define rape? And why can't she stop scratching?

Fiercely moving and slyly profound, little scratch is a defiantly playful look at how our minds function in--and survive--the darkest moments.

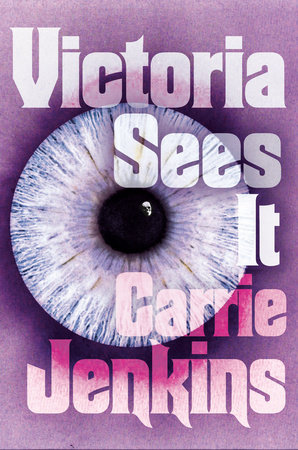

Victoria Sees It

Carrie JenkinsA queer psychological thriller from a beguiling, fresh new voice.

Victoria is unraveling. Her best friend is missing, and she's the only one who seems to care: there are clues all over Cambridge, but Deb is nowhere to be found--and the harder Victoria looks, the less she sees.

Victoria is raised in a crumbling house in England by her working-class aunt and uncle, until her academic brilliance gains her entrance to Cambridge. There, she meets her first true friend, Deb, a spacey aristocrat, and the girls create their own tiny bubble within Cambridge's strict class system. Until Deb disappears.

In her search for her friend, Victoria finds an unlikely ally--a police officer named Julie. They travel the countryside, visiting sites of suicides, murders, and accidents. But eventually, Julie's emotional demands overwhelm Victoria, and she retreats into a lonely life of academia, always teetering on the edge of emotional collapse.

Wandering through a miasma of sexism, isolation, physical and mental health issues, Victoria's story is haunted by the spectre of her mother, whose own assault and subsequent pregnancy represent a break in her contract with the world.

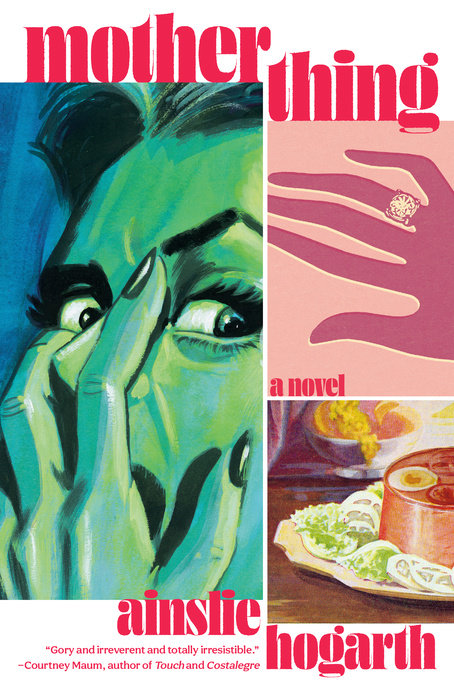

Motherthing

Ainslie HogarthA darkly funny take on mothers and daughters, about a woman who must take drastic measures to save her husband and herself from the vengeful ghost of her mother-in-law.

When Ralph and Abby Lamb move in with Ralph’s mother, Laura, Abby hopes it’s just what she and her mother-in-law need to finally connect. After a traumatic childhood, Abby is desperate for a mother figure, especially now that she and Ralph are trying to become parents themselves. Abby just has so much love to give—to Ralph, to Laura, and to Mrs. Bondy, her favourite resident at the long-term care home where she works. But Laura isn’t interested in bonding with her daughter-in-law. She’s venomous and cruel, especially to Abby, and life with her is hellish.

When Laura takes her own life, her ghost haunts Abby and Ralph in very different ways: Ralph is plunged into depression, and Abby is terrorized by a force intent on destroying everything she loves. To make matters worse, Mrs. Bondy’s daughter is threatening to move Mrs. Bondy from the home, leaving Abby totally alone. With everything on the line, Abby comes up with a chilling plan that will allow her to keep Mrs. Bondy, rescue Ralph from his tortured mind, and break Laura’s hold on the family for good. All it requires is a little ingenuity, a lot of determination, and a unique recipe for chicken à la king...

Hogarth’s way with words enlivens every page of this psycho romp... Her fearlessness and utter lack of inhibition animate the desperate longing and bitter trauma at the heart of this ghost story, administered with a steady drip of comic relief. Profane, insane, hilarious, disgusting—and unexpectedly moving.

A masterfully crafted horror novel that’s by turns humorous and deeply unsettling... Abby makes a wonderful narrator; full of wry insights and frothy humor... This dark domestic drama packs a punch.

If you took Jane Fonda’s character from the 2005 film Monster-in-Law, made her an angry ghost, and mixed that with Neil Gaiman’s Coraline, you might get Hogarth’s new novel. Fans of Jeff Strand, Grady Hendrix, and other dark-humor takes on horror will enjoy Motherthing.

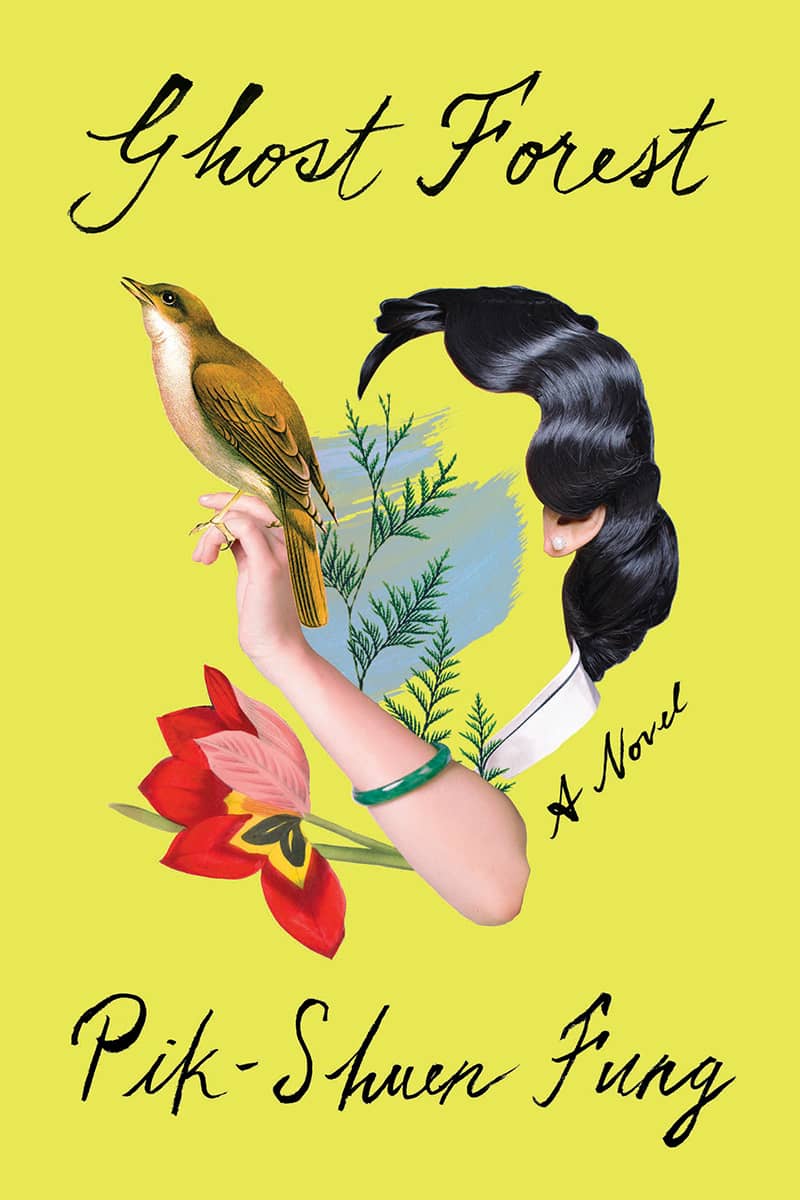

Ghost Forest

Pik-Shuen FungA graceful and indelible debut about love, grief, and family welcomes you into its pages and invites you to linger, staying with you long after you've closed its covers.

How do you grieve, if your family doesn't talk about feelings?

This is the question the unnamed protagonist of Ghost Forest considers after her father dies. One of the many Hong Kong "astronaut" fathers, he stayed in Hong Kong to work, while the rest of the family immigrated to Vancouver before the 1997 Handover, when the British returned sovereignty over Hong Kong to China.

As she revisits memories of her father throughout the years, she struggles with unresolved questions and misunderstandings. Turning to her mother and grandmother for answers, she discovers her own life refracted brightly in theirs.

Buoyant, heartbreaking, and unexpectedly funny, Ghost Forest is a slim novel that envelops the reader in joy and sorrow. Fung writes with a poetic and haunting voice, layering detail and abstraction, weaving memory and oral history to paint a moving portrait of a Chinese-Canadian astronaut family.

Newsletter

Do you like newsletters? Sign up to hear about books, news, and other updates from Strange Light and Penguin Random House Canada.